A Kidnapping Gone Very Wrong

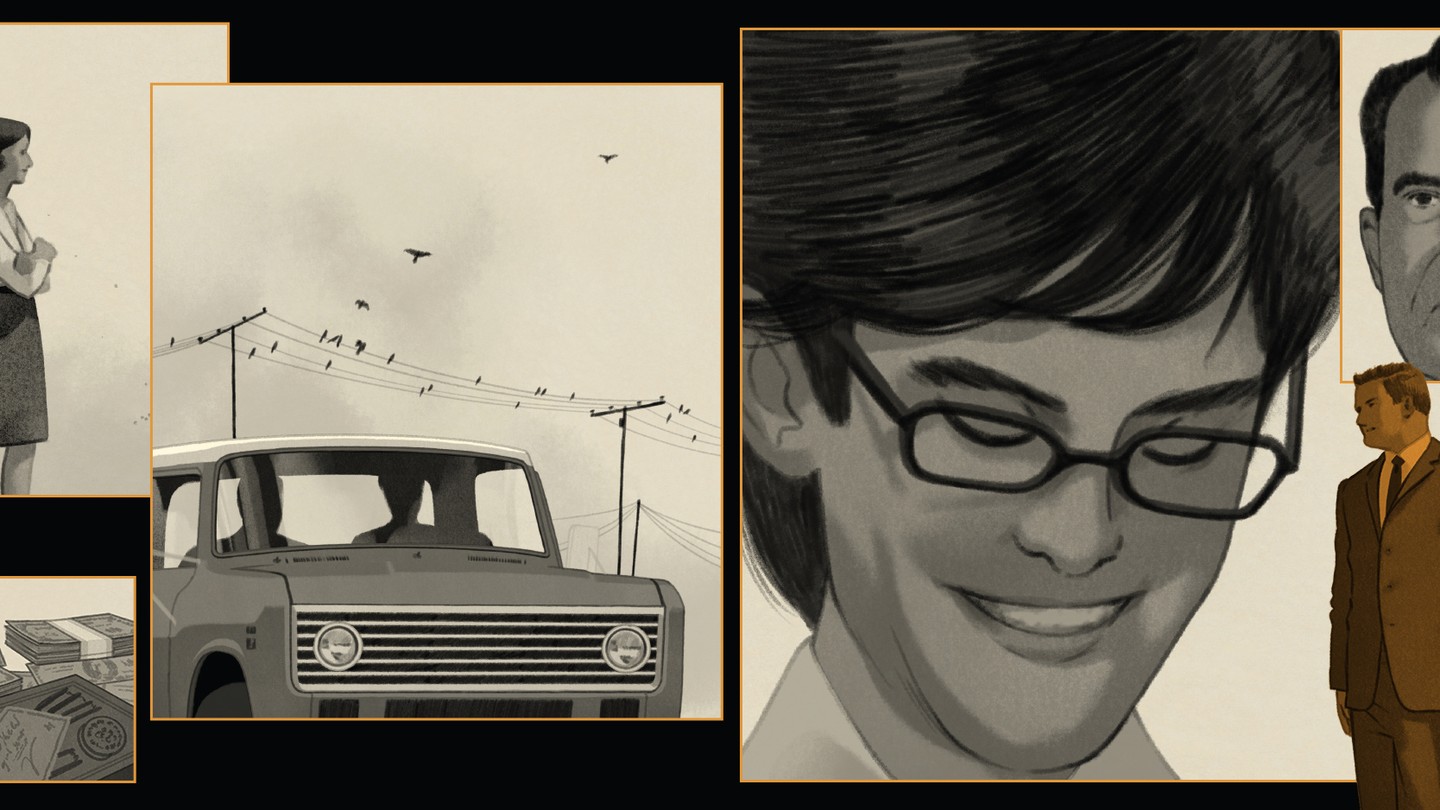

In 1974, John Patterson was abducted by the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico—a group no one had heard of before. The kidnappers wanted $500,000, and insisted that Patterson’s wife deliver the ransom.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on audm

Illustrations by Leonardo Santamaria

This article was published online on April 15, 2021.

The Motel El Encanto in Hermosillo, Mexico, served a lavish breakfast that John and Andra Patterson liked to eat on the tiled deck near their suite. The couple would discuss the day ahead over fresh pineapple and pan dulces while their 4-year-old daughter, Julia, watched the gray cat that skulked about the motel’s Spanish arches.

On the morning of March 22, 1974, the Pattersons’ breakfast chatter centered on their search for a permanent home. They were nearing their two-month anniversary of living in Hermosillo, where John was a junior diplomat at the American consulate, and the motel was feeling cramped.

After breakfast, Andra dropped John off at work. Because this was his first posting as a member of the United States Foreign Service, the 31-year-old Patterson had been given an unglamorous job: He was a vice consul responsible for promoting trade between the U.S. and Mexico, which on this particular Friday meant driving out to meet with a group of ranchers who hoped to improve their yield of beef.

At 11 a.m., Patterson grabbed the keys to a consular vehicle, a beige International Harvester truck, and headed downstairs. One of his co-workers, an administrative assistant named Luis Sánchez, saw him standing outside the building, chatting amicably with a mustached man in dark sunglasses and a blue suit. When Patterson got behind the wheel of the truck, his acquaintance climbed into the passenger seat.

An hour later, the clerk at the Motel El Encanto spotted the International Harvester traveling north on the broad boulevard that cuts through Hermosillo. He recognized Patterson as the driver: With his thick mop of sandy-brown hair and modish eyeglasses, the vice consul resembled an unkempt Warren Beatty. But the other man was unfamiliar to the clerk.

Around 2:30 p.m., Andra swung by the consulate to browse its library; she wanted to borrow some books before picking Julia up from school. She was immersed in that pleasant task when a secretary informed her that Elmer Yelton, the consul general, needed to see her right away.

Yelton told Andra that John had never shown up for his meeting with the ranchers. When the consulate reopened after its daily lunch break, the staff had discovered an envelope addressed to “Mr. Yelton” tucked beneath the front door. Inside was a two-page note scrawled on green stationery. The consul general showed this note to Andra, who could see that it was written in her husband’s hand. The words, however, were clearly not John’s own.

“I have evidently been taken hostage by the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico,” the note began, before segueing into a list of demands. The group wanted a $500,000 ransom, to be hand-delivered by Andra in two installments. The first payment of $250,000 was to be made at the Hotel Fray Marcos in Nogales, Mexico, two days later. Andra was then to fly to Mexico City, check into the airport Holiday Inn, and await instructions on how to make the second payment.

“Under no circumstances whatsoever is there to be any news release concerning my captivity before or after my release,” the letter warned. If word got out, or if the authorities attempted to intervene in any way, the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico would “execute 1 U.S. official each week or member of a U.S. official family.”

Once she’d gotten past her initial shock, Andra thought back to a strange moment in New Orleans. The Pattersons had stopped in the city in January on their way from their former home in Virginia to Hermosillo. They’d hired a babysitter to watch Julia so they could catch a movie. The film the couple had chosen was State of Siege, a thinly veiled account of the 1970 kidnapping and murder of Dan Mitrione, a USAID official who’d been teaching the Uruguayan police how to torture. During a scene in which the body of the Mitrione stand-in is found in an abandoned Cadillac, Andra had felt a jolt of anxiety. “Oh my God, that better not be you!” she’d blurted out to John, loud enough to startle other moviegoers.

John had done his best to wave off her concern. But both he and Andra knew that diplomacy had become a perilous line of work.

Word of the Patterson kidnapping reached President Nixon that evening, while he was en route to Camp David after a long week spent tangling with Watergate investigators. The president and his advisers were by now accustomed to handling situations of this nature: Patterson was the sixth American diplomat to be abducted in a little over a year.

The first had been Clinton Knox, the ambassador to Haiti, who was ambushed near his Port-au-Prince home on January 23, 1973. His kidnappers forced him to call the American consul general in the city, Ward Christensen, who was then lured into captivity as well. A deputy undersecretary of state rushed to Port-au-Prince to help negotiate for the two men’s lives. After 20 hours of talks, Knox and Christensen were set free in exchange for $70,000 from the Haitian treasury and the release of a dozen imprisoned revolutionaries.

Six weeks later, commandos from Black September—the Palestinian group that had murdered 11 Israeli athletes and coaches at the Munich Olympics the year before—stormed the Saudi Arabian embassy in Khartoum. Among the hostages they seized were U.S. Ambassador Cleo Noel and the deputy chief of mission, George Curtis Moore, who’d been attending a dinner party. The kidnappers demanded the release of numerous prisoners, including Sirhan Sirhan, the convicted assassin of Robert F. Kennedy.

A State Department official was dispatched to Sudan to establish a dialogue with the diplomats’ captors. But this was a higher-profile crisis than the one in Port-au-Prince, and Nixon, who’d come to believe that terrorism posed an existential threat to American security, decided it was time to take the hardest possible line. On March 2, 1973, while the State Department’s envoy was still in transit to Sudan, Nixon was asked about the Black September kidnappings at a White House press conference. The president improvised an answer that left his negotiator no wiggle room: “As far as the United States as a government giving in to blackmail demands, we cannot do so and we will not do so.” Hours later, the terrorists in Khartoum allowed Noel and Moore to write last letters to their wives before executing them.

Now that blood had been spilled, the Nixon administration felt compelled to double down on the president’s off-the-cuff remark and make it policy. The U.S. government would henceforth not negotiate with terrorists, even when the lives of American diplomats were at stake.

That stance was put to the test two months later, on May 4, 1973, when guerrillas kidnapped Terrence Leonhardy, the American consul general in the Mexican city of Guadalajara. Though the State Department publicly reiterated that it would not legitimize terrorists by giving in to extortion, it used diplomatic back channels to pressure Mexico to work toward Leonhardy’s safe return. After three days in blindfolded captivity, the consul general was let go in exchange for the release of 30 prisoners allied with the Armed Revolutionary Forces of the People, one of the many leftist groups devoted to overthrowing President Luis Echeverría’s authoritarian regime.

The White House chose to adopt a similar approach when confronting the Patterson affair. To maintain the optics of toughness—crucial to the president’s political survival in the thick of Watergate—the Nixon administration would refuse to provide even a penny to the kidnappers. But the State Department would be permitted to lean on the Mexican government to locate and liberate the vice consul, and it could offer to quietly assist the Patterson family should they wish to pay the ransom themselves.

This decision was relayed to Patterson’s widowed mother, Ann, who lived on Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square. She and her late husband, who’d been a successful supermarket executive, had powerful friends throughout the city, and Ann tore through her Rolodex in search of help. Within a few hours, she’d persuaded a department-store heiress to personally guarantee a $250,000 bank loan. That sum would be enough for Andra to deliver the first payment to the kidnappers, and thus buy John a little time.

A plan was made for Andra to fly to Arizona the next day to collect the ransom; she would then have ample time to make it to Nogales for her initial rendezvous with the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. Andra’s stepfather, meanwhile, would travel to Hermosillo to pick up Julia.

Andra passed the sleepless night worrying about her husband, whom she’d known since college. The two had met in the fall of 1962 while spending their junior year abroad in France. On their first date, at an Aix-en-Provence café, John ordered them both espressos in perfect French and then drank his through a sugar cube wedged between his teeth—a trick he said he’d learned from his brother-in-law in Rome. Nineteen-year-old Andra Sigerson was smitten.

That summer, John and Andra rode a Lambretta scooter across Europe. They basked on the verandas of seaside hotels, washed their clothes in the Mediterranean, and rescued a stray mutt from a swarm of bees on Mallorca. One day, as they whizzed down a mountain road toward Spain’s Costa del Sol, Andra pressed her cheek between John’s shoulder blades and thought, I can die right now, because I’ve felt the highest high a person can ever feel.

But the love affair faded once John and Andra returned to their respective midwestern universities, 400 miles apart. Andra was vexed by John’s habit of canceling his weekend visits without notice, and by the awkward pauses on their phone calls. Days before graduation in 1964, John tried to salvage the relationship by proposing on a Wisconsin bluff. When Andra declined, she assumed she’d never see him again.

Six years later, Andra left an unhappy marriage to the man with whom she’d had Julia. She and her 1-year-old daughter relocated from eastern Washington State to Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where she’d grown up. While adjusting to life as a single mother, she decided to find out what had become of John. She learned that he was now a student at Columbia Business School and arranged to meet him on the steps of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. She watched him stroll down Fifth Avenue toward the church, his hair as wild and glorious as she remembered. Andra knew they would never part again.

Andra and Julia soon followed John to Washington, D.C., where he’d found work with the ad hoc commission that was implementing Nixon’s emergency freeze on consumer prices. But the Beltway grind didn’t suit the couple, who craved the sense of adventure they’d experienced aboard their Lambretta scooter a decade earlier. The escape plan that John proposed was one he’d secretly been aching to pursue since adolescence: He would join the Foreign Service.

When he graduated from the Foreign Service’s training program, in the summer of 1973, the State Department asked him to begin his career in Santiago, Chile. But after the country’s Marxist president, Salvador Allende, was deposed in a bloody coup that September, John was reassigned to Hermosillo, a place assumed to be relatively safe for a rookie diplomat and his family.

Andra left Hermosillo at midday on March 23. Joining her on the Tucson-bound plane were two State Department veterans who’d flown up from Mexico City at dawn: Victor Dikeos, the supervisor for all of the American consulates in the country, and Keith Gwyn, a diplomatic-security agent. Neither man had ever met John, but they’d volunteered to serve as Andra’s bodyguards because they considered the Foreign Service a sacred family.

Andra and her guardians went by car from Tucson to Nogales, Arizona, where they stopped at a motel near the crossing into Nogales, Mexico. Andra had been told to wait there to receive the ransom money, which was being couriered from a bank in Phoenix. As she bided her time, a phalanx of FBI agents descended on the motel. They said they’d obtained the Mexican government’s permission to cross the border with Andra and stake out the Hotel Fray Marcos, where the payoff was to take place. The agents hoped to identify and track whoever collected the cash.

This plan made Dikeos nervous. He worried the kidnappers would execute John immediately if they detected any hint of surveillance. He was not informed of the FBI’s hunch that the person who showed up to take the money would not be a genuine terrorist, but rather someone with clandestine ties to John and Andra Patterson.

The ransom money, consisting of $50 and $20 bills stacked inside Girl Scout cookie boxes, arrived at the Arizona border motel well past dark on March 23. Andra took a taxi into Mexico and checked in at the Hotel Fray Marcos, a mere block away from American soil.

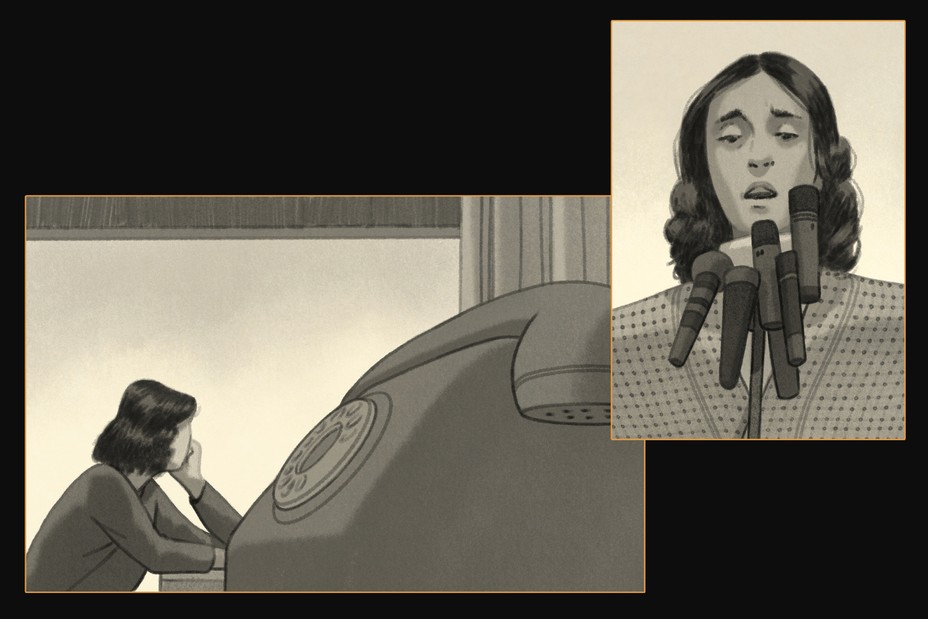

The next morning, Andra waited for the phone to ring; outside, more than two dozen FBI agents tried to remain incognito. Hours passed, yet no one came looking for the money. By lunchtime, the FBI and the State Department concluded that the payoff wasn’t going to happen, and that Andra should return to Hermosillo by car at once.

When she arrived late that afternoon, Andra learned of an important discovery that had been made in her absence: The police had found the International Harvester truck that John had been driving on the morning of his disappearance. Someone had left it at a gas station on the edge of town; there were no signs of a struggle.

The next day, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger placed a call to Andra. He was in the midst of reeling off some sympathetic platitudes when Andra cut him off to ask the only question on her mind: “Do you have any money for me?” As Kissinger tried to explain why U.S. policy precluded the State Department from contributing any funds toward the ransom, Andra stopped listening and handed the phone to someone else.

Andra settled in to await further word from the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. The U.S. government, meanwhile, took pains to heed the ransom note’s instructions and conceal John Patterson’s abduction from the public. But at a March 27 press conference in Washington, a reporter asked Attorney General William Saxbe why he had abruptly canceled an upcoming trip to Mexico. Having apparently forgotten that he’d been sworn to secrecy, Saxbe replied that an American diplomat had been kidnapped in the country and that his own security was potentially at risk.

Within hours, reporters had uncovered key facts about the kidnapping: the identity of the victim, the amount of money at stake, the name of the terrorist group involved. “U.S. Vice Consul Missing in Mexico,” blared the front-page headline in The New York Times.

Fearful of how the kidnappers might react, the diplomats in Hermosillo wrote an apologetic statement for Andra to deliver to the press. On March 29, she emerged from Elmer Yelton’s residence and faced a crowd of 30 journalists who’d assembled on the sidewalk out front. She fought back tears as she read from a note card into a bank of microphones:

I am here to appeal to the people who have my husband. I am deeply sorry that the news was made public. I will do everything in my power to ensure his welfare. Please let me know that he is well. Please contact me. And for my husband, if he could hear me …

Aware that John and Andra were fond of speaking French to each other, and of the nicknames they liked to use, the statement’s authors had concluded it with the words Giovanni, je t’aime (“John, I love you”). But that phrase struck Andra as not quite right, so she improvised a final line more reflective of her yearning and her fortitude. Giovanni, je t’attends: “John, I am waiting for you.”

Two hundred Mexican police officers combed the desert beyond Hermosillo, hoping to find John Patterson. They discovered no sign of the vice consul, though they did arrest some members of the 23rd of September Communist League, a Marxist guerrilla group responsible for attacks throughout the state of Sonora. The authorities had recently killed one of the group’s leaders, and a rumor circulated that the Patterson abduction might be an attempt at revenge. Mexican police interrogated the captured insurgents, but their brutal style of questioning yielded no useful clues.

Patterson’s own government, meanwhile, doubted that Mexican revolutionaries had played any role in his disappearance. From day one, the FBI had suspected that it might be dealing with a “self-kidnapping”—an elaborate hoax engineered by the Pattersons to steal money from John’s family.

The bureau’s agents had found the kidnappers’ modus operandi odd, starting with the fact that no one had ever heard of the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. Weirder still was the group’s stated aversion to publicity: Media coverage is the lifeblood of terrorism, the means by which small movements make their political aims known.

FBI investigators had also reviewed a sketch of the man who’d been spotted in John Patterson’s truck on the morning of March 22 and had decided he was likely a white American, based on his facial features and formal manner of dress. Agents combed through airplane passenger lists and the logs of rental-car agencies, searching for American citizens who might have been in Hermosillo when Patterson vanished. The list of potential suspects included a copper-mining executive, the landlord of a mobile-home park, and the owner of a Lake Tahoe ski resort, all of whom eventually cleared themselves with alibis.

FBI field offices from Seattle to Milwaukee to New York were ordered to dig into the Pattersons’ backgrounds. The agents assigned to this task documented the nature of the couple’s relationship, which had reignited while Andra was still technically married to her first husband, and which included a child who was not John’s own. They also noted Andra’s apparent affinity for leftist causes. She “admitted to participating in various ‘Rad-Lib’ demonstrations and was against the war in Vietnam and admitted participating in demonstrations against the war,” an agent wrote in his summary of an interview with Andra. At an agency where J. Edgar Hoover’s reactionary politics still held sway, the Pattersons may have harbored too many progressive ideals to be trusted. The FBI’s leading theory was that the Pattersons had masterminded the whole affair.

That theory, shared by Mexican authorities, was soon leaked to newspapers on both sides of the border. “Police Assure that Disappearance of U.S. Vice Consul is a Self-kidnapping,” one blunt headline stated. The Justice Department began to discuss how to prosecute the Pattersons once the scam had reached its end. “If it is determined to be a hoax, prosecutive action would most likely be in the Phoenix division,” the FBI director’s office noted in an April 5 memo.

John’s alleged kidnappers were silent until April 10, when a man who spoke perfect English with a slight Texas twang called the consul general’s residence in Hermosillo and asked for Andra. Elmer Yelton’s wife, Jo, who had the poise of a woman with decades in the field, took the phone instead and said that Andra wasn’t there.

“I—they will give her a second chance,” the man said, referring to Andra. “She is to go to Rosarito in Baja … We are both in Baja … She is to stay at the Rosarito Beach Hotel … She will be contacted there Friday … John will—and I will be—released Sunday, if she does not cause trouble.”

Jo Yelton pressed the caller to furnish some proof that John was still alive. But the man kept insisting that he was a hostage too, and could offer nothing beyond the message he’d been ordered to convey. “But please, ah, these people came very close to harming John and I because of this,” he said. “And they are very serious.”

The FBI had plenty of reasons to consider the call fishy, not least the fact that it traced back to a telephone exchange in San Diego. But Andra Patterson was adamant that she be given the chance to make the payment—this time without companions who might scare away her husband’s captors. After taking a light plane to Tijuana with Victor Dikeos and Keith Gwyn, Andra drove alone to the Rosarito Beach Hotel.

Over the next few days, Andra sat by the hotel’s pool, a McDonald’s bag filled with cash always by her side. But as had happened in Nogales, no one ever came to take the money, and Andra left, dejected.

On May 6, an envelope addressed to Elmer Yelton arrived at the Hermosillo consulate; the postmark revealed that it had been mailed from California on April 30. The letter inside was written on the same green paper as the original ransom note, but the handwriting was not John’s. “Two times we gave you chances to free him and two time [sic] you hoped to trap our fighters but we know what you do when you do it,” the letter read. “Fail to do as we instruct and death is now his only release.” The author directed Andra to return to the Rosarito Beach Hotel and check in under the name “West.” If she had the $250,000 payment, she would be taken to meet her husband.

There was a problem, however: The letter stated that Andra had to be back in Rosarito no later than May 3, a date now three days in the past. The slow delivery of the mail had apparently invalidated the kidnappers’ offer before it could even be made.

For the second time, Andra felt she had to reach John’s captors through the media. On May 17, she spoke to the press and stressed that she was willing to do whatever the kidnappers desired. “I ask only one thing first,” she said. “For some proof or evidence that they indeed have my husband and that he is all right.”

That proof would never come. As Andra was making her plea to the press, the FBI was having a radical change of heart about the case. The bureau’s agents in Southern California were beginning to zero in on a person of interest, a 40-year-old American who clearly hadn’t conspired with the Pattersons—and who, just a year earlier, had been feted as a national hero at the White House.

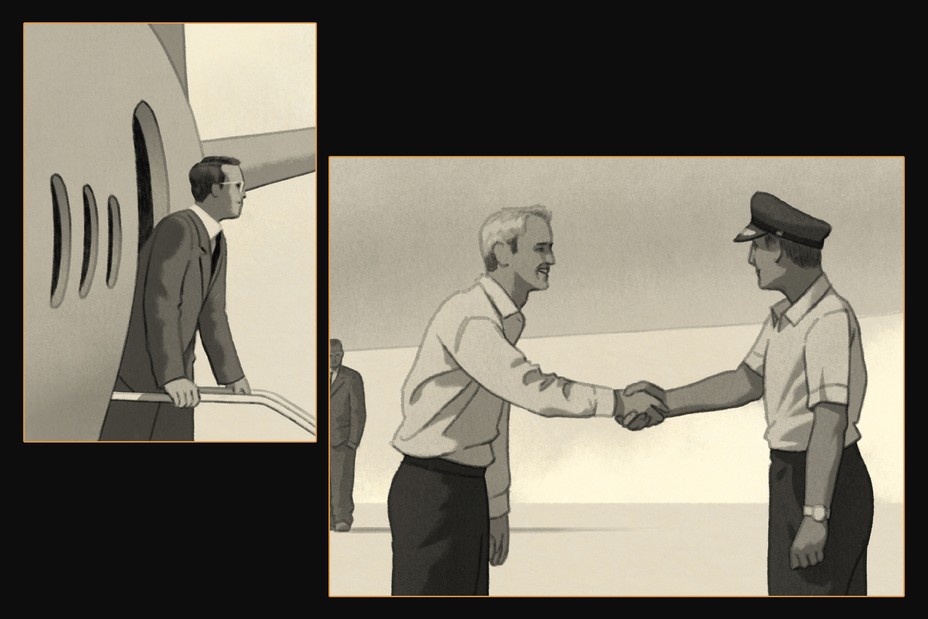

On March 14, 1973, three C-141 cargo planes touched down in sequence at Clark Air Base, in the Philippines. The vessels carried 108 American prisoners of war, freed by North Vietnam as part of the Paris Peace Accords. Many of these men had spent years in captivity at Hỏa Lò Prison, better known as the Hanoi Hilton. Their homecoming was meant to be a moment of catharsis for a war-weary American public.

One by one, emaciated men in sky-blue work shirts emerged from the planes and saluted the ecstatic crowd from atop the boarding stairs. The loudest cheers were for Lieutenant Commander John McCain, the most famous of the freed prisoners, whose limp betrayed the horrors of the abuse he’d endured.

With the audience’s attention focused on the heroes at the front of the plane, few noticed a lone figure exit through the rear door of the last C-141 to land. An unimposing man on the cusp of middle age, he hustled to a waiting bus without responding to any shouted questions from the press. Up until that moment, most everyone familiar with the story of Bobby Joe Keesee had assumed he was long dead.

Keesee hailed from a microscopic town in the Texas Panhandle. He dropped out of the eighth grade and, at the age of 17, enlisted in the Army just in time to be shipped off to the Korean War. Though he yearned to be a paratrooper, Keesee spent his nine months in combat as a standard infantryman. Upon his return to the U.S. in 1953, he decided to make the Army his career and spent the rest of the decade doing stints at bases in Japan, Germany, and Iceland as he attained the rank of sergeant. He earned his parachutist badge, qualified as a sharpshooter with an M‑1 rifle, and learned how to operate the flight simulators used to train military pilots.

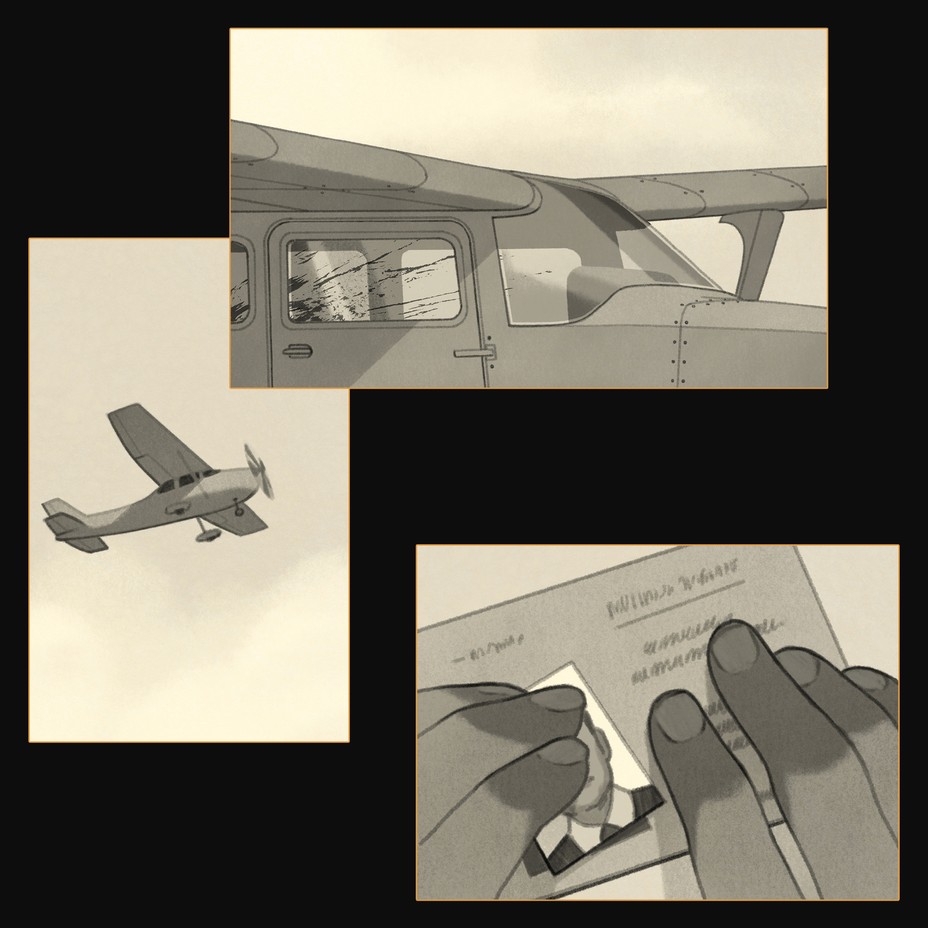

The most notable aspect of Keesee’s Army career was the manner in which he chose to quit. In January 1962, Keesee went AWOL from Fort Huachuca, in Arizona; stole a car; and embarked on a 13,000-mile road trip that took him as far north as Alaska. After two months on the lam, he wound up in Albuquerque, where he rented a Piper Comanche airplane. He told the owner that he needed to fly his wife to Carlsbad to visit an ailing relative, and that he’d be back by sunset. Every piece of that story was a lie.

Keesee flew east toward Florida, paying for fuel along the way with kited checks. His last stop in the U.S. was at Marathon, in the Keys, after which he made the short hop to Havana. Upon landing, he professed his desire to live in a socialist paradise and requested asylum.

Fidel Castro’s secret police were unmoved by Keesee’s pleas. They seized his plane, jailed him for 49 days, then put him on a flight to Miami. Keesee was arrested at the airport and extradited to Austin, Texas, where he faced a 153-count federal indictment that carried a possible life sentence.

At trial, Keesee mounted an unusual defense: He contended that he’d acted at the behest of the CIA, which had recruited him to carry out a mission to destabilize Castro’s regime. “I was dumbfounded when they arrested me,” Keesee said on the witness stand. (The CIA insisted that it had no records of Keesee.)

Keesee spouted other fictions too, with the apparent aim of appealing to the jury’s sense of patriotism. He claimed, for example, to have earned a Purple Heart in Korea after suffering a grievous head wound in combat. (His lone war injury, to one of his arms, occurred during a pickup soccer game.) Keesee’s lies seemed to have the intended effect. He was ultimately convicted of just a single count of theft and sentenced to a mere five years in prison; he was out in less than three.

After another stint behind bars, for stealing a shipment of parachutes from Fort Bliss, in Texas, in 1965, Keesee moved to Phoenix and found work as a cabinetmaker. But his dalliance with blue-collar normalcy did not last long.

In September 1970, Keesee turned up in northeastern Thailand. Masquerading as a movie producer, he chartered a small plane with two pilots on the pretense of scouting film locations in the jungle. Twenty minutes into a flight near the Laotian border, Keesee brandished a pistol and ordered the pilots to take him to a beach near the North Vietnamese city of Đồng Hới. It seemed an absurd request given that the U.S. was mired in a long-running conflict with North Vietnam that had cost more than 50,000 American lives.

Once the plane came to rest on the white sand, Keesee jumped out holding a leather briefcase and walked toward a nearby row of huts. After dodging gunfire during takeoff, the pilots glanced back to see dozens of startled villagers encircling the doughy, bespectacled Keesee, the only American within a hundred miles.

The North Vietnamese villagers took Keesee prisoner and turned him over to the army, which understandably assumed that he was a spy. Interrogators used all manner of torture to get Keesee to cough up information about his mission: They knocked out his teeth and tore out his toenails. But since he was just a cabinetmaker afflicted with a pathological need to insert himself into global events—a need that blotted out all logic and reason—Keesee could provide nothing of value to satisfy his tormentors.

He wound up in solitary confinement as one of the Hanoi Hilton’s few civilian inmates. Since the North Vietnamese never acknowledged that they had him in custody, both his family and the U.S. government thought he’d been killed soon after landing near Đồng Hới. His appearance alongside John McCain and the other released POWs in the Philippines was a shock to all who remembered his bizarre odyssey.

The Thai government made noise about extraditing Keesee so that he could stand trial for hijacking the plane he’d chartered in 1970. But it never made a formal request, to the relief of American officials, who opposed the move. Despite his muddled backstory, Keesee possessed the veneer of heroism by virtue of his proximity to more noble POWs. And in 1973, a defeated America was in desperate need of heroes.

Keesee was flown to Travis Air Force Base, in California, where he made a show of kissing the honor guard’s American flag before receiving a $1,792 payment from the government for his time in captivity. Two months later, he attended a welcome-home party at the White House. Inside a tent on the South Lawn, he quaffed champagne and gorged on sirloin with the likes of Sammy Davis Jr., Phyllis Diller, and John Wayne. The highlight of the evening came when a well-oiled President Nixon made a toast and cracked a joke about having ended the Vietnam War so Bob Hope—also in attendance—could be home for the holidays. The president then joined Irving Berlin in a raucous rendition of “God Bless America.”

Keesee moved to Huntington Beach, California, where he rented an apartment, bought a yellow Ford Mustang, and obtained numerous lines of credit. He participated in parades and other civic functions where former POWs were in high demand. Eventually, though, he was forced to look for paid work. On his application to an Orange County cabinet shop, he listed his previous employer as “U.S. Govt” and his job description as “Classified.” He landed the job despite the obvious red flags.

But he once again soured on life as a working stiff. In early January 1974, he paid a visit to a co-worker named Greg Fielden, a 19-year-old with a decent command of Spanish. Keesee told the teenager that he needed his help pulling off a caper that would make them both rich. It involved a trip to Mexico.

Keesee and Fielden crossed the border in Keesee’s Mustang on January 16, 1974. Their destination was Hermosillo, where Keesee’s father had retired. Under the guise of being a cattle trader, Keesee had traveled there a few times in recent months to scout out the American consulate, even going so far as to introduce himself to a senior diplomat named Louis Villalovos. During their conversation, Villalovos mentioned that the consulate would soon be welcoming a new economics officer, a Columbia Business School graduate named John Patterson. Keesee told Fielden that they would lure the inexperienced Patterson out to the desert and hold him for ransom.

But their timing was off. When Keesee and Fielden asked for Patterson at the consulate, they were told he was still en route to Hermosillo and wouldn’t be starting work for another week. The duo left the city without their would-be hostage.

Fielden told Keesee he didn’t want to participate in any future kidnapping attempts, and Keesee decided to abandon the idea. But then a tragedy made him reconsider: On March 6, Keesee’s father drowned while fishing near Hermosillo, and Keesee went to Mexico to arrange for the body’s repatriation to Arizona. While sifting through his father’s estate, he found a Remington 12‑gauge shotgun.

On March 19, three days after burying his father in Phoenix, Keesee returned to Hermosillo and checked into the Hotel Gandara. He paid another visit to the American consulate, where he struck up a dialogue with John Patterson about the Sonoran cattle industry. On the morning of March 22, he called Patterson and talked his way into tagging along for the vice consul’s meeting with the ranchers.

Patterson had been trained to be wary of people who looked like they might have ties to Mexican terrorists, not well-dressed Americans. As he climbed into the International Harvester with his genial new acquaintance, Patterson had no reason to think that anything was amiss.

Like so many criminals whose ambition exceeds their diligence, Keesee was undone by a careless error: When he’d checked into the Hotel Gandara, he’d done so under his own name. When the FBI belatedly got its hands on the hotel’s registration cards, its agents naturally wondered why a convicted felon had been hanging around town.

The FBI approached Luis Sánchez, the administrative assistant who’d spotted Patterson’s conversation partner on March 22, and showed him an array of photos of mustached white men. Sánchez picked out two and said that either could be the man he’d seen outside the consulate. Both photos were of Bobby Joe Keesee, taken years apart. The recording of the April 10 phone call to the consul general’s residence proved useful too. The FBI played the tape for Keesee’s older brother, who identified the voice as Bobby Joe’s.

On the morning of May 28, the FBI arrested Keesee in Huntington Beach as he left his apartment to go to work. A search of his car turned up a pair of handcuffs and two shotgun shells.

Rather than claim total ignorance of the case, Keesee confessed that he was the person who’d written the April 30 letter that had instructed Andra to return to the Rosarito Beach Hotel. He insisted, however, that he’d only sent the letter because he’d felt sorry for Andra and wanted to give her a shred of hope. He otherwise denied knowing anything about the kidnapping.

Andra was in New York retrieving Julia when she learned that her husband’s alleged kidnapper was being held on $100,000 bail. The news did not erode her faith in the inevitability of her husband’s safe return. She and Julia traveled to Mexico City and became temporary guests of Victor Dikeos and his family, who occupied a plush villa with a trampoline in the backyard. While Julia began ballet classes, Andra devoted herself to apartment hunting. She vowed to friends that she was willing to grow old in Mexico if need be; she wouldn’t leave the country without John.

On July 8, 1974, a peasant wandering in the scrublands north of Hermosillo noticed what looked like the carcass of a large animal. But when he pulled close to the mass of blood, bone, and skin, he realized that he’d stumbled upon a human body half-buried in the dirt—a male with a thick mop of sandy-brown hair.

The coroner in Hermosillo left no room for doubt that John Patterson had finally been found. He matched the body’s teeth to dental records sent from Philadelphia. A gold wedding ring was found on the ground near the body, inscribed with the initials JSP and AMS, as well as the French words Mon Destin. The cause of death was blunt-force trauma to the head.

Henry Kissinger sent an Air Force jet to Hermosillo to transport Patterson’s body to Washington, D.C., for burial. Andra accompanied her husband’s flag-draped casket on the journey to Andrews Air Force Base. The honor guard on the tarmac, the funeral at Rock Creek Church, the awkward embraces from dignitaries she’d never met—all of it was a blur for Andra as she tried to reckon with the emptiness that lay ahead.

Federal prosecutors added murder to the list of charges against Bobby Joe Keesee. They built a seemingly airtight case, the centerpiece of which was an affidavit from Greg Fielden in which he described the failed kidnapping plot from January. Investigators also tracked down the shotgun once owned by Keesee’s father at a pawn shop. An analysis of the gun’s stock revealed specks of human blood.

Prosecutors contended that once Keesee had had Patterson under his physical control, he’d realized that the vice consul would surely identify him if released. Keesee, the prosecutors wrote, had seen only one way out of his predicament:

It appears that Keesee handcuffed Patterson and marched him off into the desert. Patterson must have realized at this time that Keesee intended to kill him because all of the evidence points to a struggle. His broken glasses were discovered next to a bush about 100 feet from his grave …

It must have been when Patterson began to struggle, that Keesee, with ten years’ Army experience as a paratrooper and an expert in the use of arms, delivered the crippling butt stroke to Patterson’s face which broke his glasses and knocked out his front teeth. After Patterson fell to the ground, Keesee must have then smashed in the back of his head and dragged his body into a small gully nearby.

In the midst of pretrial preparations, however, prosecutors seem to have suffered pangs of self-doubt. They lacked an eyewitness to the murder or physical evidence that tied Keesee to the crime scene. (The dried blood on the shotgun could not be definitively matched to Patterson.) The muddled nature of the kidnapping investigation also threatened to prove problematic: The defense might try to discredit the FBI by harping on the weeks it had spent focused on John and Andra as the plot’s organizers.

Rather than risk the humiliation of losing at trial, the U.S. attorney’s office in San Diego cut a deal. Keesee agreed to plead guilty to a single count of conspiracy to kidnap, specifically linked to the extortion letter he’d mailed from San Diego on April 30, 1974. In exchange, the government dropped all the other charges, including murder.

In advance of sentencing, a court-appointed psychiatrist evaluated Keesee. The doctor described him as a sociopath who was “clever enough to surround himself with verbal smokescreens.” Yet even the psychiatrist wound up bamboozled by his subject. “Mr. Keesee has a good deal on the positive side of the ledger—physique and physical health, intellect and engaging personality, and a versatile education largely obtained ‘the hard way,’ ” he wrote in his report. “Society may be able to profit from his services in five to ten years.”

At his sentencing hearing on April 28, 1975, Keesee was offered the customary opportunity to make a statement. The words he offered were superficially contrite yet oddly passive. “There’s nothing more I can say,” he declared. “I got involved in something that I realize was wrong.” Moments later, the judge sentenced him to 20 years in prison. The Justice Department assured the Pattersons that Keesee would serve the maximum term possible. But it would not make good on that promise.

In late 1998, a champion powerboat racer named Harry Christensen placed a classified ad in Flying magazine. Christensen, who also owned a boat-manufacturing company near Arizona’s Lake Havasu, had recently purchased a new Piper Cheyenne turboprop, and he was looking to sell his old Cessna 340. The most promising response came from a man who called from Las Vegas. He introduced himself as a property developer named Bobby Joe Keesee.

Christensen flew to Las Vegas on January 5, 1999, to pick up the 64-year-old Keesee and take him to Lake Havasu City. The two men agreed to close the deal the next morning. Christensen’s wife, Debbie, and his son, Jeff, expected to see him at work later that morning with Keesee’s $300,000 check in hand.

When the afternoon rolled around without any trace of him, they alerted the police and went looking for him at the airport. They were told the Cessna had taken off around 8 a.m. and had landed in Winslow, Arizona, to refuel. It was unclear where the plane had gone from there.

That evening, Debbie and Jeff received a call from the proprietor of Coronado Airport in northeast Albuquerque. The Cessna had landed there that afternoon and was now parked on the tarmac. The police searched the empty plane and found a pool of blood in the passenger area, as well as a travel bag containing Keesee’s pilot’s license and a .38-caliber pistol clip that was missing bullets.

The next day, Keesee was arrested by FBI agents while driving on Interstate 25 near Las Cruces. His pockets contained Christensen’s driver’s license, which he’d altered by gluing on his own photograph, and a gold Rolex engraved with the initials HMC.

Keesee had been paroled in January 1986, having supposedly proved his trustworthiness by working in a prison business office. Over the next dozen years, Keesee had orchestrated a series of daring scams: He had set up a fake company to purchase $634,000 worth of copper; he had posed as a Federal Emergency Management Agency official to steal 2,000 feet of gold wire; he had tricked a New Jersey aviation company into selling him a cargo plane that he’d hoped to offload to Mexican drug traffickers. Each con ended with his arrest. But Keesee had never served more than a few years in prison for any of those crimes.

After his arrest near Las Cruces, Keesee swore that Christensen had been alive when they’d parted ways. But on May 2, a rancher found Christensen’s remains while grazing his cattle in a desolate patch off New Mexico’s Route 44. An autopsy revealed that Christensen had been shot twice in the chest and once in the head.

Even Keesee couldn’t talk his way out of trouble this time. To avoid the death penalty, he agreed to plead guilty to a range of charges including murder and air piracy. A sentence of life without parole meant that Keesee’s career—a case study in the incoherence of evil—had finally come to an end.

Andra Patterson barely survived her first year as a widow. She moved back to Virginia and lived under an assumed name, fearing that Keesee might have associates who wished her and Julia harm. As she mourned her husband, she often took solace in a fantasy in which she spotted John and Keesee driving through Hermosillo in the International Harvester. Andra envisioned herself racing out into the boulevard to pull John from the vehicle and spiriting him back to the safety of the Motel El Encanto. Whenever the reassuring power of that reverie wore off, a wave of crushing sadness followed.

Andra’s grief, so staggering in the years right after Mexico, gradually receded into the background of her busy life. She worked at the State Department, where she edited an in-house newsletter, and she eventually remarried. She also became an accomplished painter; her work was once displayed at the U.S. embassy in Kuala Lumpur.

I first contacted Andra through the website she maintains to showcase her art. A few months later, she agreed to meet me for coffee in New York. Less than a minute after we sat down, she cut off my feeble attempt at chitchat to say that she was reluctant to dredge up her most searing memories and share them with the world. She was worried not just about the psychic toll of opening up about the events in Hermosillo, but also about her personal safety. The last time she’d received any word about Keesee, back in the mid-1990s, he was out of prison; what if he tracked her and Julia down after seeing one of his old crimes brought to light?

I told Andra about the murder of Harry Christensen, whose name she’d never heard before. And I was also able to assure her that Keesee was no longer a threat to anyone: He had died of lung cancer in a prison hospital in December 2010. No one had claimed his body.

Andra eventually consented to a series of interviews at her home near Washington, D.C. During the first of these, she showed me a file box marked The Case, which had been sealed up in her attic. It contained a trove of artifacts that she had preserved: affidavits, telegrams, newspaper clippings, a letter of condolence from President Nixon, an annotated map from the European scooter trip with John. Andra told me she’d recently started sifting through the archive for the first time in 40 years. It was painful, of course, to be reminded of how her world had been smashed apart by a sociopath. But there was also joy to be had in reacquainting herself with the person she’d once been—a person who had not wilted in the face of the incomprehensible.

“That young 31-year-old woman, she acted with no help, no one to hold her; her best friend was missing,” she said. “But she acted—I acted—completely honorably throughout that whole period. And I love her.”

This article appears in the May 2021 print edition with the headline “The Diplomat Who Disappeared.”